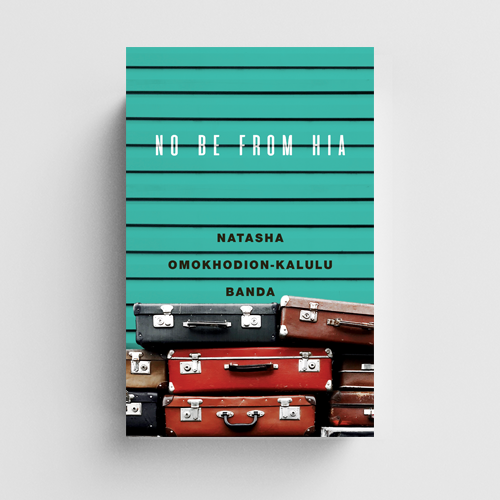

No Be From Hia Chapter 1

CHAPTER 1

MAGGIE OLUWASEUN AYOMIDE

LUSAKA, ZAMBIA, 1991

I wake with a start to the sound of adult voices in the corridor of our little flat. My father’s familiar bass voice and my mother’s defiant responses reverberate through the thin walls. A third voice, my mother’s friend from next door, Chonta, is pleading with my father. The commotion cannot be ignored. I remember where I am, and a heavy, sinking feeling opens in my heart, like an anchor dropping through deep water, farther and farther, until it plops at the bottom of a murky floor.

I have not seen my father since we left London, and that was a long time ago. I was still in grade one. After a long ride in a black cab behind red lights that blurred into snaky lines and a foggy smokescreen from exhaust pipes, mum and I burst through the airport’s doors and winded our way through the luminous jungle of Heathrow.

It was the middle of the night, and it seemed we ran and ran for miles. We were the last ones to get on the plane after mum shouted at the red faced man who had hair plastered to his forehead. She shouted, and then she cried, and then she begged, and finally they opened the gate for us. I dropped my soft doll Eleanor because we had to hurry, and I’ve never seen her again.

I’m now in grade three, and I’ve almost forgotten the rhythmic thump-thump of dad’s heartbeat through his freshly pressed button-down shirts and the croon of his voice as he read to me before bedtime. His chin was always prickly after a shave, and I’d push my finger into the dimple at its centre when he came back from the barber.

I float out of my room, still hoping that this is an extension of my dream, that I will wake again to realise it’s not happening. The hem of my floral nightdress shakes violently. I stand still, trembling, unable to take in what I see. Our once perfect world is upside down.

My mother stands at an angle, her neck in the forceful crook of my father’s left arm, like the innocent person in the movies whose body is being used as a bullet shield. My father holds a knife to her neck. To be more accurate, a sand knife, the one Ba Mailesi uses to prepare thickly buttered bread in the mornings, to cut through chicken thighs and backs as she makes us stew, nshima, and impwa. The sand knife which she so carefully rubs against the dry rock outside the kitchen door to ensure it is sharp enough to slice through bone. Its tip now pierces the soft skin of my mother’s neck, drawing a thin line of blood.

Father is crying; mother is crying. Chonta, the neighbour is pleading, her voice shaky but steady – one moment she is begging, the next chastising. Finally, she settles on a convincing tone, the kind you use on a child when you want them to do something for you but are not sure what the power of their own volition will ultimately reveal.

My father is not listening. ‘Stella, you are still my wife. Maggie is our only child. You will do as I say and come with me to Nigeria!’ His eyes are wild with fury, and without his spectacles, they look unhinged from their sockets. His once smooth chin is a knotted mass of curls. He smells different, like a man who will do anything in this moment. He reeks of desperation.

‘Oh, so today I’m your wife? Where have you been, Abs? It’s been over a year since we last saw you. Look around; we’ve moved on! We’ve survived without you! Kill me if you must! The only person going to Nigeria is you!’ my mother spits through clenched teeth.

‘Please, Mr Abisola, put the knife down,’ Chonta says.

The scene carries on like this for what feels like many hours, but it is probably over in five minutes. Warm lines of urine slide down my thighs, and my nightdress clings to my legs. My eyes tear. My nose burns, and it is moist. I say nothing. I stand there.

Finally, he sinks to his knees. My father releases his weapon, and it clinks on the floor tile. He cries softly into his palms. ‘Let’s go home, Stella. We are a family.’

Weeks in darkness ensue. My existence dwindles to endless days that turn into nights, to faraway voices and whispering shadows. I am being kept ‘safe’ at homes of family friends. The custody case is in court. Every time they say it, in muted tones, it sounds like a bad disease. Custody. They look at me like I’m the man in my little Bible who Jesus healed from leprosy. Custody doesn’t sound so bad to me – in fact, it makes me smile.

I imagine mum and dad in a courtroom full of yummy custard, the pair of them before a judge explaining what happened. In my imagination, dad is leaning back in a chair with his hands steepled while he adjusts his round spectacles with his forefingers. I imagine he is wearing a tie, even though he loathes them and has never owned one. Mum must be perched upright. Her face, brown, and bony, cold and composed like the wooden carving in our living room. Her hands, one over the other, resting against the colourful stripes of her chitenge skirt.

I picture the judge with the face of my Zambian grandfather – Grandpa Charles – big, dark, and round. I have only seen him in photographs and history textbooks.

The judge of my imagination has a curly, white wig like the ones everyone wears in ‘My Book of Nursery Rhymes’. He listens to them while he scoops gooey yellow custard out of a large wooden bowl. He wipes his brow because the air is hot. I know he will understand that grownups fight sometimes, and then he will give them sage advice. He will let them go, and then they can both come and get me. Maybe we can go back to London. Or maybe mum will say yes, and we can all go to Nigeria. Or maybe daddy will nod his head and join us here in Lusaka.

Mummy finally comes to pick me up one day in a gleaming white Cressida. She comes right in between the day and the night, when the sky is a mix of watermelon and tangerine, when the sun is about to give way to the moon, when the birds flock and flap their way to their nests.

She’s smiling and happy. She glows bright, and I don’t know if it’s because I haven’t seen her in a long time, but she looks golden, like she’s been scrubbed and polished and scrubbed again. She looks like an Egyptian goddess. Like an angel. She puts my bag in the back of her new car, and she thanks the people I have been staying with. She says to me, ‘Let’s go home’.

I agree, even though I don’t know any more what that is.

Home is fleeting, beautiful, and fragile. It flutters away like the orange and black butterflies in the garden that I try to catch with my open palms.

After that, I do not see daddy again. Not for many, many years. My parents’ lives continue, each of them finding new lovers and new lives, fresh starts – playing the game of divide and multiply, leaving me in no man’s land. A remnant of dreams gone wrong, of pain and despair. A family that will never again be. Or was it ever? Maybe it is all in my imagination.

This I do know, though: it is the beginning, even though it feels like the end.